1. Could you start with a broad picture of Madagascar’s mining sector and its strategic importance to the national economy?

Today, mining represents roughly five percent of Madagascar’s GDP, but its weight in external accounts is far greater: minerals account for more than forty percent of national exports. That makes the sector a key pillar of our balance of payments. Structurally, we speak of two tiers: large scale mining, which are capital-intensive operations, and the small and medium segment, which includes a wide constellation of operators across the country. Beyond foreign exchange, mining also has strong regional spillovers, jobs in communes and regions, service ecosystems around the sites, and local procurement. In direct employment terms, the sector contributes on the order of twelve percent of jobs, an estimate that is evolving but gives a sense of scale.

2. What are the government’s current priorities for developing, and regulating, the industry?

The general policy of the State, set out under the guidance of His Excellency the President of the Republic Andry Rajoelina, is unambiguous: promote large-scale mining while professionalizing small-scale mining. To deliver on that, we first had to modernize the legal and regulatory framework so our ambitions match global realities. Mining is inherently international, capital comes from abroad and products are marketed abroad, so we must be aligned with international standards and investor expectations.

In 2023 we adopted a new Mining Code (Law No. 2023-007). During 2024 we followed with the implementing decrees, on the gold regime, the permit regime, and other implementing texts. The texts are now in place; our focus is execution.

Regarding mining licenses, we preserved the principle of the “first-come, first-served” for regular permit applications, but we added a strong “use it or lose it” rule. For example, if you hold an exploitation permit and do not start work within two years the State can revoke it. For exploration, minimum exploration expenditures are mandatory; if they are not met, the perimeter is reduced automatically. These measures are meant to end a past era where Madagascar was full of paper permits and short on actual production.

For large strategic areas we created a different track. Article 136 allows the State to reserve zones for mining promotion and to award them through a competitive process. These calls for tenders will screen for work programs and financing plans upfront, so we allocate ground to parties who can actually deliver. Article 138 also provides for a State participation in the project company awarded through this route. The State is entitled to an allocation of 10 percent of the share capital of the legal entity awarded the contract, which holds the mining permit. This non-dilutable participation cannot be considered as granting any special privilege to the said bodies. That equity stake is not a deterrent; on the contrary, it aligns the State as a partner and gives investors stability.

To clean up the mining cadastra, on March 19 of this year the Council of Ministers approved the cancellation of 998 mining titles, across exploration, exploitation, and artisanal categories, for non-compliance with the law. The purpose is to free ground for serious investors under the new rules.

3. Transparency and governance are recurring investor concerns. What concrete steps have you taken, including vis-à-vis EITI?

Transparency is now hard-wired into the law. Where adherence to the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) was once a voluntary approach, the new code makes EITI compliance mandatory. Last week we launched an online platform for declarations, covering, for example, beneficial ownership filings required in the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) process.

Digitization is the other pillar. We are phasing out paper permits entirely. Titles are now electronic, secured with QR codes that resolve to an authoritative URL in our registry. Any change of ownership or substance is updated at the source, no more stamps and “lost title” games that open the door to fraud. Each operator will have a unique identifier; all interactions, applications, fee payments, royalty declarations, are tied to that ID, giving us a live, auditable trail.

With World Bank support, we are building a modern mining cadastra and e-services portal so that, in due course, applications and payments can be made online. Internally, I created a Directorate for the Fight Against Corruption, and we are standardizing procedure manuals and service diagrams for each unit, so applicants know exactly what is required, reducing discretion and the temptation to “ask someone to help.” We have also translated the Mining Code into English and Chinese, in addition to the French and Malagasy versions. Ignorance breeds opacity; clarity reduces the space for abuse.

4. The code also speaks to ESG. What are the new social and environmental obligations?

Several elements are now explicit, and enforceable. First, you cannot start work with a mining title alone; you must have an environmental and social permit, obtained after public hearing. That reduces conflict risk by defining responsibilities at the outset.

Second, corporate social responsibility is no longer optional. Articles 241–243 mandate CSR commitments, formalized in a tripartite convention between the operator, local communities, and the administration. This ensures that CSR budgets respond to local needs rather than being outsourced to consultants with minimal local impact.

Third, local content and skills transfer are mandatory. At least 80 percent of project employees must be nationals (with 20 percent foreigners), and operators must invest in training and in sourcing goods and services from Malagasy companies where feasible. Job creation is not just a macro headline; it builds local ownership of projects.

Finally, on the State side, we are developing economic models for each major project, price scenarios, production plans, capital expenditure, debt service, tax and royalty flows, so the government has a clear view of fiscal returns over the life of mine. That informed our recent negotiations with large operators. We want investors to make money, this must be sustainable, but balanced frameworks ensure the country shares in the value created.

5. From an investor’s perspective, where are the most promising opportunities, and for which commodities?

Geologically, Madagascar is blessed with both a sedimentary basin and a crystalline basement, which host very different resources.

Hydrocarbons are in the western sedimentary basin, onshore and offshore. We have a verified commercial discovery of heavy oil in the mid-west with estimated reserves of 1.7 billion barrels; moving south, the crude becomes lighter and natural gas appears, with initial gas identifications underway in the far south.

On the crystalline basement and along the east coast, the heavy mineral sands are significant. Ilmenite, the feedstock for titanium metal, prized for its strength-to-weight ratio in aerospace, is abundant from Fort-Dauphin up to Diego Suarez, along the east coast. Rio Tinto operates at Fort-Dauphin, and additional projects are advancing further north. Those same sands host monazite, a phosphate containing rare earths (and thorium/uranium). Madagascar has both light rare earths (such as praseodymium and neodymium, critical for EV motors) and heavy rare earths.

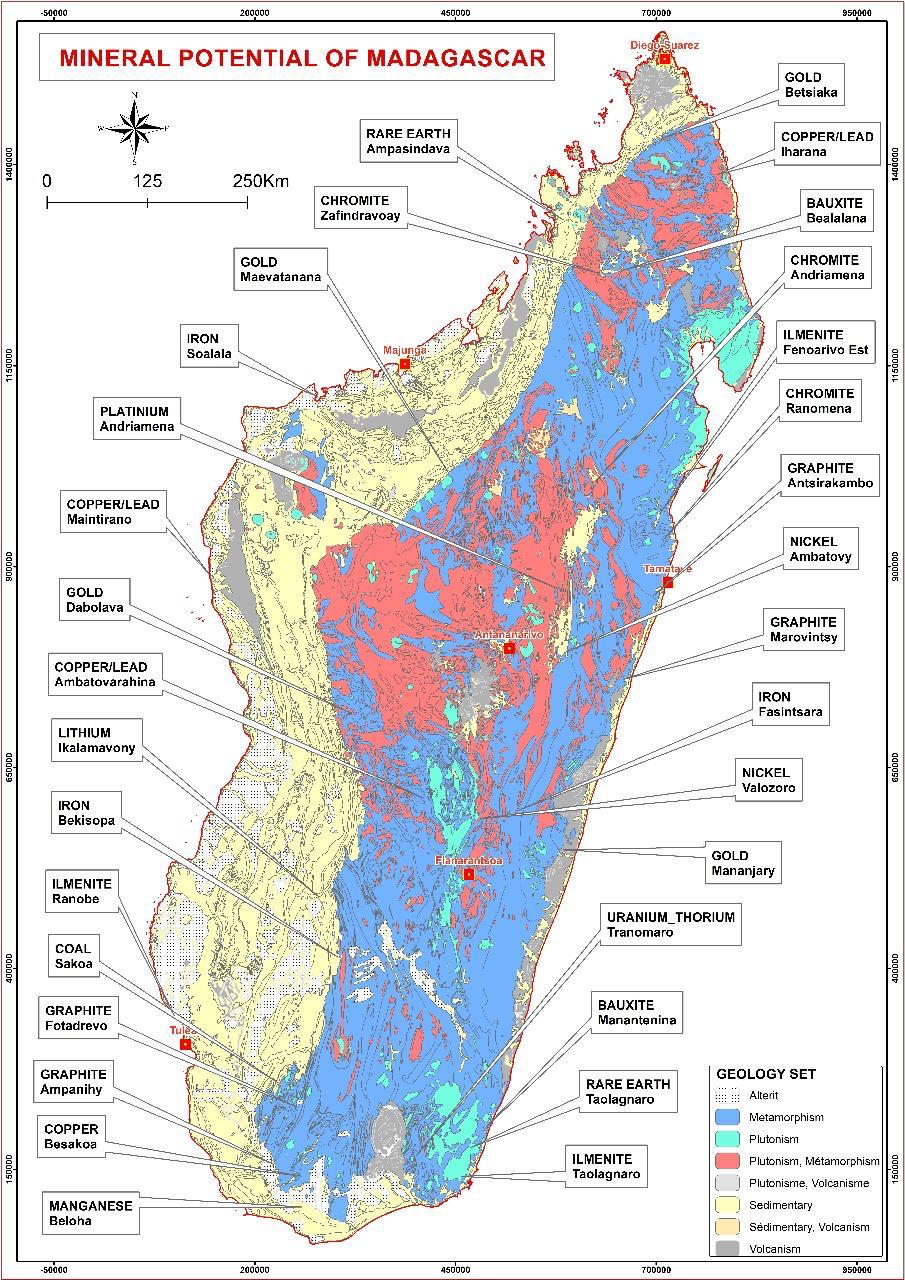

We are also graphite-rich. Madagascar ranks first in Africa and fourth globally for graphite reserves. Deposits occur on the east coast and in the south; Australian and Canadian groups are advancing projects toward production. With the recent cancellation of non-compliant titles, substantial ground in graphite, and in manganese, has been freed for new entrants. Interest in aluminum-bearing ores is growing, and we hold two major iron ore prospects where Australian players are active. We will share a deposit distribution map; it helps investors visualize the portfolio.

6. You mentioned competitive tenders for reserved areas. How will you balance competition with investor certainty?

Reserved-area tenders will prioritize capacity and commitment. Bidders must present robust work programs and financing plans; awards will come with clearly defined obligations and timelines. The State’s ten percent participation in tendered projects aligns our interests. For large investments, we also have a dedicated law on major mining investments that provides legal, fiscal, and customs stability for the duration of the project.

Additionally, above a defined threshold, one hundred million dollars of investment, investors benefit from customs franchises on equipment imports, using a generic list agreed upfront. We are establishing inter-ministerial committees to accompany large projects, with the explicit mandate to facilitate permits and authorizations across the administration. It’s about speed with integrity.

7. What role do Gulf partners, especially from the UAE, play in your strategy?

We are open to all investors who can help transform potential into wealth, and the Gulf is a priority partner for Madagascar. The government has already initiated a strategic partnership with the United Arab Emirates in energy, Masdar has signed for a solar park, and discussions are advancing in tourism and agriculture, including a fertilizer plant endorsed recently by the Council of Ministers. In mining, exploratory dialogues are underway; while we have not yet signed a sector-specific MOU, momentum is building. The opening of our embassy in Abu Dhabi and new air links will only deepen ties. Your readership includes precisely the decision-makers we want to engage through transparent, bankable opportunities.

8. A final message to Khaleej Times readers: why is now the time to invest, and how will your ministry facilitate the journey?

Madagascar’s mining sector is at an inflection point. We have decided, clearly, that our subsoil must contribute to the well-being of our people. That requires investment, competence, and partnership. We have put the enabling framework in place: a modern code; enforceable ESG; competitive tenders for strategic ground; “use it or lose it” discipline; electronic titles and online processes for transparency; and stability regimes for large investments. We’ve cleared out non-performing titles and opened space for serious players. And we are setting up the Madagascar Geological Bureau to organize and disseminate geological data.

On transparency, our new EITI website, will publish all binding texts automatically upon promulgation. The Mining Code is available in Malagasy, French, English and Chinese. Our door is open, and our team is here to help credible investors navigate from concept to operation.

We want mining to be an engine, around each large mine, service economies form, skills deepen, and communities advance. If you bring capital, technology, and respect for our standards, Madagascar will meet you with clarity, speed, and partnership. The tools are ready. You are welcome.